In the realm of photography, Indrias Getachew Kassaye stands as a luminary in a masterful weaving of art and social impact in his work. His lens gracefully encapsulates beauty in the ordinary, magnifying the resilience of communities in a creative challenge of preconceived notions about Africa. Kassaye’s work is driven by the desire to transform perceptions of Africa through the power of imagery, while reinstituting agency in people who are often spoken for rather than listened to.

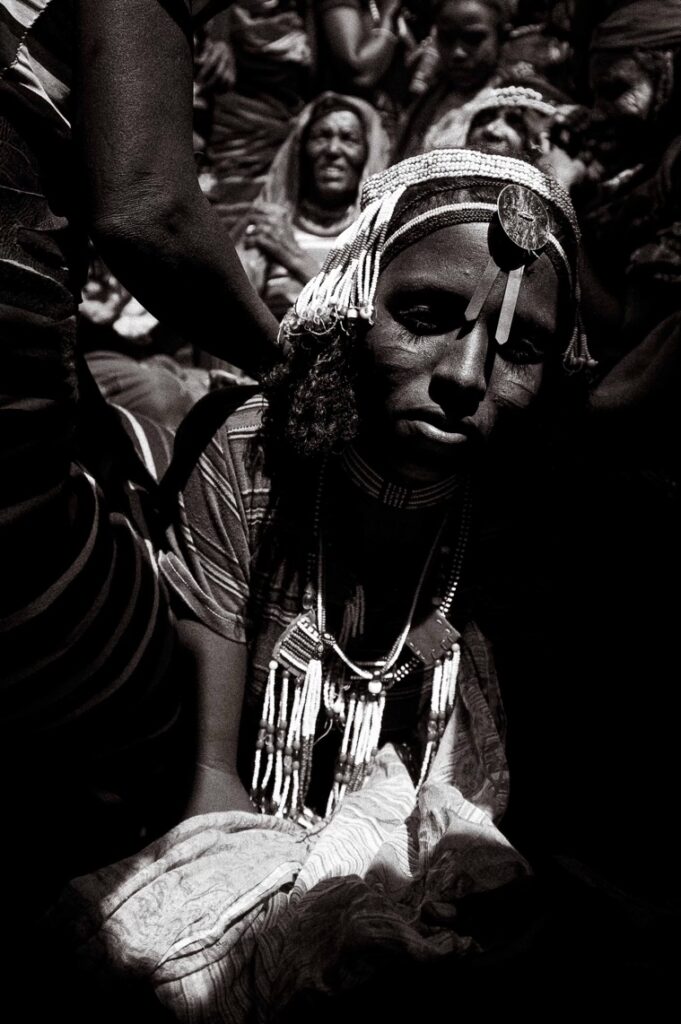

Hawa on her wedding day. Awash Fentale District, Afar Region 2012

In the realm of photography, Indrias Getachew Kassaye stands as a luminary in a masterful weaving of art and social impact in his work. His lens gracefully encapsulates beauty in the ordinary, magnifying the resilience of communities in a creative challenge of preconceived notions about Africa. Kassaye’s work is driven by the desire to transform perceptions of Africa through the power of imagery, while reinstituting agency in people who are often spoken for rather than listened to. Curious about the origins of his passion, I asked “Why photography?”. In a fond reflection on his childhood, Kassaye noted that his desire to create always existed, but not through the mediums introduced to him during art classes at school. Interestingly, his early artistic endeavors were not the most successful, leaving him in constant awe of those who could create with their hands. Despite this, he always had a keen eye for visual storytelling and decided to paint his picture differently, ultimately finding his medium in cameraphotography and the 110 mm camera he got for his ninth birthday.In high school, he upgraded to a 35mm SLR, enrolled in photography classes to fulfil mandatory art credits, and spent hours in the school library pouring though photography books, including the intimate and powerful portraits of people on the fringes of ‘acceptable’ society by Diane Arbus,, and Dorothea Lange’s depictions of people in migratory crisis. He would later discover the works of Malian photographer Seidu Keita and the brave, bold war-time storytelling of Iranian born National Geographic photographer Reza. Important lessons in style, technique, and the power of images to transform mindsets and sensibilities.

Women elders place a drum on the bride’s back, singing and chanting before leading her to the groom. Awash Fentale District, Afar Region 2012

Living in America, in both high school and later on in Philadelphia where Kassayehe attended the University of Pennsylvania, Kassaye experienced the broad misconceptions of Africa brought on by global media culture that only covers Africa in times of extreme crisis, like the 1980’s famine in Ethiopia,You Ethiopian’Ethiopian’ became an insult used by black children squabbling on the streets of West-Philly.Instances like these informed his desire to challenge dominant narratives through the convergence of art and social justice in his own work.

Women elders singing and chanting over the bride before bringing her to the groom

From a series of exhibitions and photojournalism to multi-media production, working on communications with UNICEF and multiple NGOs across Africa, Kassaye’s career has taken many forms with the power of creativity at its core. Kassaye’s work has covered sensitive subjects like efforts to end harmful practices like female genital cutting, child marriages, Ebola, the impact of war and recovery efforts. All of these happen within the context of everyday life lived by families and communities where there is not only hardship and sorrow, but also love, laughter, joy and dignity – and even in the most difficult of circumstances, these do come through, and with that the certainty that good things are in store. Another is Breathe in the Roots, a documentary following an African American man seeking answers to questions about his heritage in Ethiopia. As Kassaye observed, “If kids from Philadelphia saw Ethiopia through the eyes of someone they could relate to, it would be instrumental in changing their perception of Ethiopia, perhaps instilling a sense of pride in being of African descent.”

To Kassaye, there is nothing quite like art in its capacity to spark interest, diving into the subconscious to encourage a shift in perspective. Beyond aesthetics, his work illustrates photography’s capacity to be a powerful tool in driving change. When asked what Black Euphoria means to him, Kassaye noted that the very phrase stands in stark contrast against overwhelmingly negative narratives that have surrounded Black people for centuries: “This exhibition isn’t just about joy but about relief, release, and freedom. While remaining cognizant of the challenges we face, Black Euphoria is an opportunity to celebrate ourselves and be celebrated by each other, and by the world.” The theme of the exhibition is embodied in his series of grayscale photographs, a poignant call to the viewer’s attention that things are in flux; the photographs depict movement and shadow, where celebration and the looming threat of circumstance meet in a moment of euphoria.

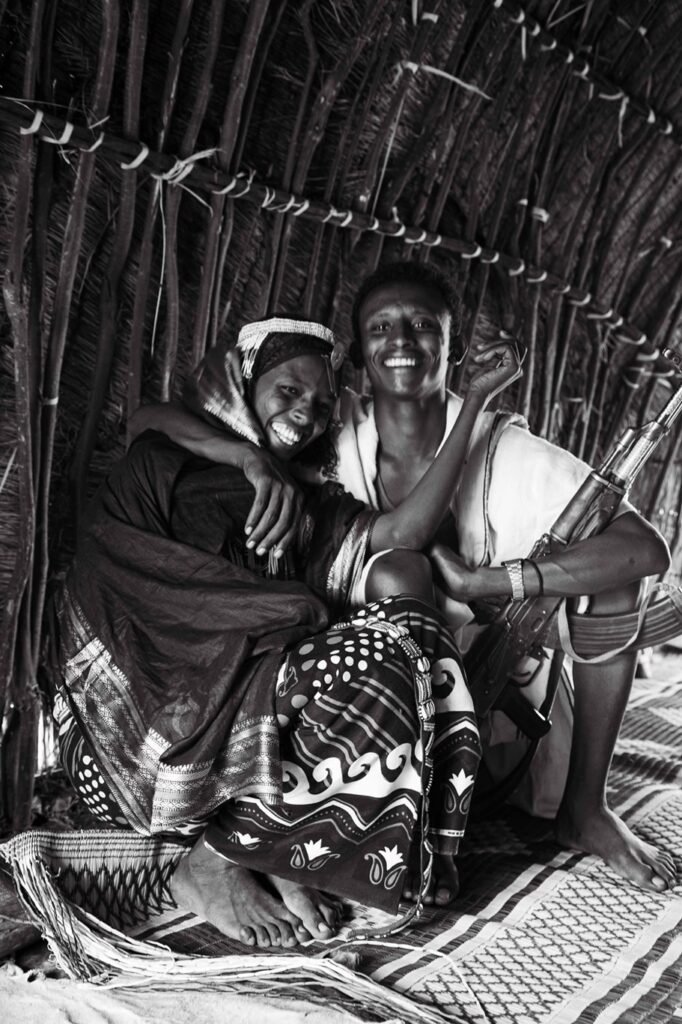

Hawa (left) and Inihaba (right) making history as the first couple in their community to be free of FGM/C. Awash Fentale District, Afar Region 2012

Black Euphoria is not just an exhibit. It represents a journey through the resilience of the human spirit, highlighted in the transformative power of Kassaye’s take on visual art. His holistic approach to photography centers the humanity of people he photographs, so as not to reduce human beings to objects of pity. The pieces he presents are part of a continuing effort to build bridges between Africa and the diaspora, in an ode to the euphoria that Black people of the country and the African diaspora deserve to experience in a world which often misunderstands and misrepresents us.

Leave A Comment