Johannesburg was in the wake of escaping the bubble of cultural isolation they had been facing for the past forty-six years when the first Johannesburg Biennale was established in 1995. From May 1948 to 1994, South Africa was ruled by the Nationalist Party which instituted a harsh form of racial, cultural, political and economic segregation, which was called apartheid. Apartheid was a country-institutionalized method of racial segregation imposed by South Africa’s Nationalist Party. The policy caused years of violent internal conflict, economic and cultural sanctions, and social economic struggles, especially for its Black majority. Apartheid coincided with the Cold War and worked in various ways of cause and effect. United States President Harry Truman’s foreign policy priority was to limit Soviet expansion; however, at the same time, the U.S. did not intervene within the anti-communist South African government’s agenda to maintain an ally against the Soviet Union in southern Africa. When the Nationalist Party came into power in 1948, they imposed massive restrictions against non-white South Africans. Protests from non-white South Africans (violent or nonviolent) were banned, Black political parties, the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC),were outlawed, and their leaders imprisoned in 1960, while racial segregation demonstrated similar parallels with the United States’ Civil Rights Movement.

In 1990, Nelson Mandela was released unconditionally from prison after 27 years; in 1994, after the Nationalist Party had lost its support, the African National Congress gained power and Nelson Mandela was elected as the country’s first Black President. South Africa began to lead more democratically, with international partners beginning to reintegrate with South Africa culturally and economically.

There are two editions of the Johannesburg Biennale: Africus (1995) and Trade Routes: History and Geography (1997). The first Johannesburg Biennale, Africus, was hosted only one year after the end of apartheid, defining South Africa’s cultural, economic, and political reentry into international dialogue. Intended to boost national moral e and posit South Africa as a center of rich culture, the Biennale garnered mixed reviews. Many believed that the biennale was not a good use of South Africa’s limited resources, and that the country was not ready for such ventures.

At the time of establishment, the artistic infrastructure of Johannesburg was fraught with internal conflict. The country was divided into Black community artists (self -taught) and white artists who were classically trained by international art schools. When reflecting on the curatorial strategy of the Biennale , Rosengarten wrote:

Overseas curators were invited to work with South Africans in an openended way, and this led to one of the most interesting features of the Biennale, a hybridisation of categories and a brave attempt to problematise the relationship between hegemonic and local culture. In some cases, the results were a disastrous and incomprehensible hodge-podge, like the Flemish show, curated by Bart De Baere and Simphiwe Myeza. In others, notably in the French show, curated (inevitably) by Jean-Hubert Martin, with trainee curator Clive Kellner, the exchange of work and the opening of boundaries was so effective that one lost any specific notion of where the show began and ended. The Spanish show, ‘Black Looks White Myths’ curated by Octavio Zaya, Danielle Tilkin and Tumelo Mosaka, inverted the terms of the brief and included only four Spanish artists, alongside 19 South Africans.

Both local and international curators were invited to submit proposals; fifteen international curators took on the role of volunteer and local trainee coordinator. This was supposed to create a bridge between organizers and South Africans; however, the chosen international curators did not have the cultural or lived experiences to bridge the gap and act as translators between the Biennale and the local South African community. The hybrid nature of this collaboration produced both good and bad exhibitions. For example, the Flemish show that was curated by Bart De Baere and Simphiwe Myeza is referred to as a “disastrous and incomprehensible hodge-podge”. However, the French show, curated by Jean-Hubert Martin with trainee Clive Kellner, received outstanding reviews and was referenced as a continuous circulation of dialogue.

The Biennale faced issues of funding, execution, and marketing. South African art critic Ivor Powell had a curatorial project that was supposed to be executed at the 1st Johannesburg Biennale (with gallerists Rayda Becker and Ricky Burnett) but was ultimately cancelled due to funding. In a 1995 New York Times article, Ivor Powell discusses orchestration of the biennale not only through an art critic lens, but an economic one as well. He writes the following about the economic position of the biennale:

THUS FAR THE BIENNIAL HAS operated on a budget of about $1.4 million, which has been both inadequate and tardy, forcing the organizers to stagger from crisis to crisis. Basic funds must still be found to bring in a clutch of the poorer participants. The budget wasn’t always this tight. Christopher Till, the city’s culture director, and Lorna Ferguson, the director of the biennial, managed to run up thousands of dollars for international travel before Ms. Ferguson’s appointment had even been announced. And subsequently they rang up many thousands more — even though about $177,000 was spent bringing foreign curators to South Africa to discuss the event …There has been an upsurge of criticism. Despite its politically correct pretensions, some critics say, the biennial was doing much more to promote the glitz of internationalism than the development of its own art. In addition, none of the major corporate sponsors of the arts in South Africa has contributed money, and the private sector has produced only one etenth of the $1.6 million anticipated. Tensions mounted steadily until, in the middle of 1994, Ms. Ferguson broke Mr. Till’s nose with a well-placed punch during one of many altercations. The result is that the biennial may overrun its budget by about $1 million.

He claimed that the Biennale put too much focus on international artists, when the focus should have been on national and intracontinental artists instead. The Biennale also faced issues of legitimacy; international countries such as the United States and Britain chose artists deemed patronizing, artists that they wouldn’t have chosen to represent them in a Western art event.

Art critic Thomas McEvilley’s essay in the exhibition catalog for Africus, “Here Comes Everybody ,” came with a highly optimistic approach. He included reflections of curators Christopher Till and Lorna Simpson that discussed the mission of the Biennale to serve as: “a type of visual diplomacy that introduces the people of the world to one another in their living reality”. Despite the catalog’s optimistic tone, the catalog itself was messy, disorganized, and unprofessional. It posed the question, “Why a biennale ?” It addressed questions that were raised about the purpose and ethos of the exhibition, rather than an accompanying publication to support the exhibition itself. Till and Ferguson conveyed their sense of moral obligation to expand the world of possibilities for South African artists and to position South Africa as an innovative arts and culture hub. The catalog was 300 pages long and contained commissioned essays by European and American critics, mini-essays on exhibitions, charts and diagrams of cultural analysis and policy, art historical articles, and photo essays.

Artworks were improperly catalogued and archived, resulting in a lack of an organized bibliography with sloppy citations. Critics, curators, and art historians were simply listed in the catalog by name, but no achievement/affiliation/context as to why they were chosen to participate in Africus. The aforementioned moral duty expressed by Till and Ferguson was deemed as contradictory due to the nature of the catalogue and essay; the writing style associated with the Biennale was unnecessarily complicated and lacked the vocabulary to engage in dialogue with the Johannesburg and South African population that the organizers claimed they wanted to cater to.

The Second Johannesburg Biennale

The second Johannesburg Biennale, Trade Routes: History and Geography, opened in October 1998 with Nigerian-born curator and critic Okwui Enwezor as artistic director. Much expanded from the first edition, it featured artworks by more than 160 artists from 63 different countries, 35 of which were African. Enwezor divided the biennale into six separate sections held across two cities with a two-hour flight time – Johannesburg and Cape Town to position South Africa as a “globalized biennale”. The Biennale included independent films from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Europe, and a performance from Robyn Orlin, where she portrayed Icarus wearing a metal harness, motorcycle helmet, and pink tutu, flying across the main Biennale Pavilion, which was hosted at the controversial Electric Workshop. This second Johannesburg Biennale sought to correct the shortcomings of the first biennale. Enwezor’s mission was to: “examine the history of globalization, by exploring how economic imperatives of the last five hundred years have produced resilient cultural fusions and disjunctions, exploring how culture and space have historically been displaced through themes of colonization, migration, and technology.”

Already, this edition of the Biennale had been proven to have a completely different feel than the last Johannesburg Biennale. Enwezor’s great reputation re-encouraged patrons and workers in the arts to attend the international event . Curators included: Gerardo Mosquera from Cuba; Hou Hanru from China, based in Paris; Yu Yeon Kim, based in Seoul and New York; Octavio Zaya from Spain, who has worked with European, Latin American and African artists who lives in New York; Kellie Jones from the USA; and Colin Richards from South Africa.

Enwezor wanted to avoid the common mistake of fetishization and didn’t want to create that sort of hierarchical relationship between the audience and the object. There was also concern about the overtly violent tones of nationalism around the world and how this may hinder the selection process. There was concern about the rise of nationalism that was being executed violently at the time, and how this might hinder the selection process. Consequently, curators were instructed not to curate exhibitions based solely on nationalism.

Curator Kellie Jones’ show was called Life’s Little Necessities and explored the way women artists discussed a myriad of issues by using installations in the 1990s. Within this exhibition, American artists Lorna Simpson and Jocelyn Taylor used film to explore issues of the body and erotica, while Nigerian artist Fatimah Tuggar and South African artist Veliswa Gwintsa explored the narratives of the domestic space.

This biennale was preceded with the 1997 – 1998 financial crisis, which caused ripples in Johannesburg’s city-wide infrastructure, resulting in the government not being able to pay for electricity. Due to this, Trade Routes was forced to close a month early; however, it reopened a month later.

At the opening remarks, neither President Nelson Mandela nor Deputy President Tabo Mkebi spoke. Public government interface between the Biennale and its audience would have promoted the agenda of the African National Congress and served as a landmark for how far South Africa has come after the social, cultural, economic, and political isolation of apartheid.

Although Trade Rotes: History and Geography was reviewed significantly better than Africus, the Biennale was out of touch with the realities of what was still going on in the country. South Africa was facing internal diasporic and displacement issues; the exhibition focused on diasporic citizens of the world and issues of displacement that didn’t reflect upon South African ideals and life. In fact, many of the featured artists were based in New York City, London and focused on Western intellectual frameworks, not South African or Pan-Africanist frameworks.

The central show, Alternating Currents, was the largest exhibition and brought internationally acclaimed artists to South Africa, such as Gabriel Orozco, Felix Gonzalez Torres, Beat Streuli, Sam Taylor -Wood, Shirin Neshat, Stan Douglas, Rhona Pondick, Ghada Amer and Eugenio Dittborn. It was co -curated by Enwezor and Octavio Zaya. The exhibition was dominated by installations and videos, however almost all media types were present.

Notable installations of the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale include: Victorian Philanthropist Parlour, 1996 -97 by Yinka Shonibare. Victorian Philanthropist Parlour was an installation that featured a Victorian parlor upholstered with African batik. The work demonstrated the culture as a literal and specific construction. Batik is thought to be native to Africa, however, the technique is originally from Indonesia and landed in West Africa by way of Holland and Britain through colonialism, migration, and trade.

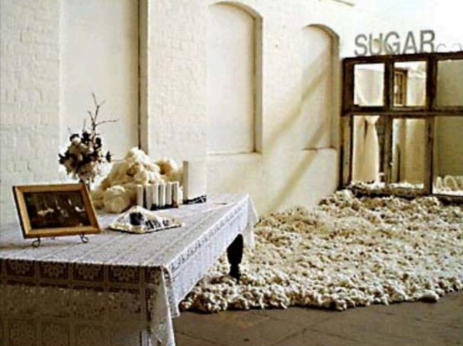

Marc Latamie is a Martiniquan artist whose work reflected the human impact of the global trade in coffee, sugar, and cotton in a recreation of an import and export office.

Vivian Sundaraman is an Indian artist whose installation used text and photographic images printed on steel to underscore the effects of global commerce and the overflow of unaffordable consumer goods.

Untitled (Sea Island Series), 1991–93 by Carrie Mae Weems is a series that represents the legacy of African Americans and West Africa. Weems documents her search for her African ancestry who took her through a West African pilgrimage along the once-called Slave Coast from Senegal to Ghana and the Ivory Coast.

Teresa Serrando’s video artwork is most reminiscent of migration and memory; thousands of butterflies are captured migrating northward, super-juxtaposed with images of human migration, famine, war, and other disasters every few minutes.

The Biennale extended beyond the city of Johannesburg and included two shows in Cape Town, the former home of South Africa’s Nationalist Party and its white rulers who had imposed decades of apartheid policies.

Despite the diverse intellectual and innovative artwork presented, the Biennale still operated through a colonial lens, to its own detriment. The curatorial work operated under the guise of apartheid, which is to be understood given South Africa’s burgeoning structure as a newly independent country.

In an Art Monthly review of the 1997 Johannesburg Biennale, Black British critic and scholar Eddie Chambers writes:

The nearest that black South Africa gets to being curatorially included in the Biennale is in the form of Colin Richards, a white curator, writer and Senior Lecturer at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. This point is important because the construction of this Biennale does nothing to interrupt the formidable set of cultural and political assumptions that disempower black South Africans, regarding them as culturally worthless and lacking intellectual ability. So black South Africans, with aspirations to curate exhibitions see those aspirations denied and trampled upon. But the worst of this only becomes apparent when we realise that Black South Africa is brutally marginalised twice over: black South Africa has, by and large, not been asked to participate in this Biennale and neither has black South Africa been addressed by this Biennale.

The introduction of apartheid in 1948 inflicted colossal damage on the pysche and on the fabric of South Africa and now, when the country is emerging from one of the most traumatic periods of its history, the Johannesburg Biennale steadfastly refuses to acknowledge apartheid and its legacy within the curatorial constructs of these exhibitions. This slap in the face for black South Africa is compounded by the Biennale publicity material. The banners and posters that one sees around Johannesburg and Cape Town have absolutely no resonance with the people. Black South Africa scarcely knows that a Biennale is taking place within its midst, because, suite simply, no -one has bothered to tell them.

The Biennale attempted to reconstruct the way that citizens could think about themselves situated in the economic, political, and cultural climate of post-apartheid South Africa.

In Bisi Silva’s review of the Johannesburg Biennale, she reflects upon the Biennale’s engagement with local citizens in Johannesburg, in South Africa, and even with international patrons. A lack of advertising resulted in a gap in attendance in Biennale events such as public programming, even among the most avid art lovers. She reflects:

As one might expect, the Biennale was haunted by questions regarding the relevance of contemporary art to the real issues of life in Johannesburg, Cape Town, and the surrounding townships. Despite the progress of recent years, the majority of South Africans are still disenfranchised, and receive negligible benefits from cultural events like this. For future Biennales, Johannesburg needs to find a format that will connect to is African neighbors without the forfeit of its global aspirations. “Trades Routes: History and Geography” was a beginning.

“Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations – Office of the Historian.”

Becker, “The Second Johannesburg Biennale.”

Both Ferguson and Till were experienced art world practitioners; Ferguson had run and grown Tatham Gallery (South Africa) from a regional museum to nationally recognized collection in her eighteen-year tenure and Till served as the Director of Culture for the Transnational Municipal Council (TMC).

Rosengarten, “Inside Out.”

“ART; Curtain Rising In South Africa, Isolated No More – The New York Times.”

Claasen, “AFRICUS: Johannesburg Biennale, 1995.”

silva, “The Johannesburg Biennale.”

Binder and Haupt, “Okwui Enwezor – Interview, 1997.”

Jones, “Life´s little necessities.”

“Second Johannesburg Biennale.”

“ART; Curtain Rising In South Africa, Isolated No More – The New York Times.”

Chambers, “Johannesburg.”

silva, “The Johannesburg Biennale.”

Leave A Comment